The French of North America

It’s nothing short of a historical miracle! On a continent where English and Spanish are the majority and official languages, from North to South America, Québec is like a Gallic village proudly hanging onto French, which it has made its sole official language. English and other languages are also spoken in the province, particularly in the cities.

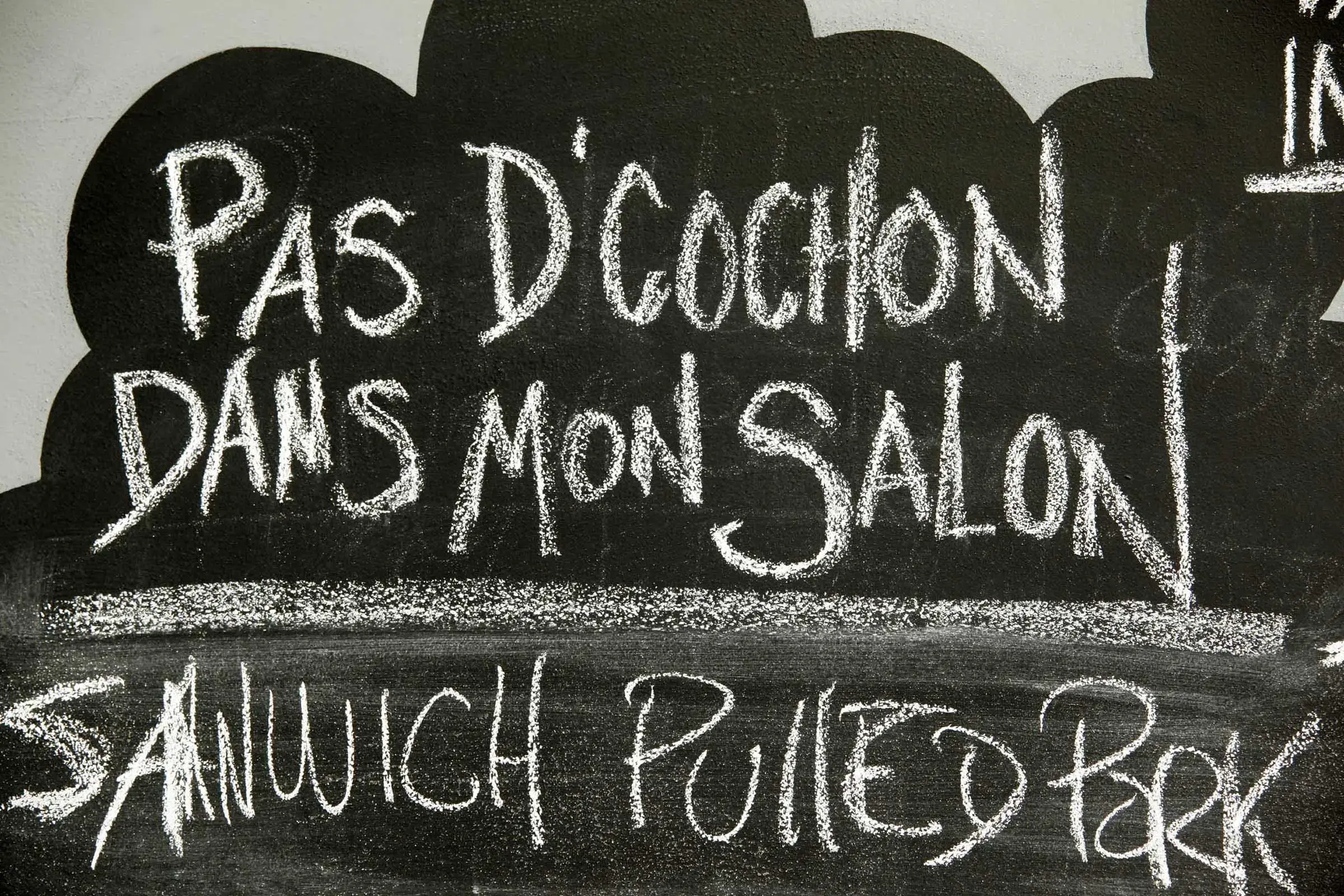

Québec has a little surprise in store for French-speaking visitors from elsewhere: you’ll have no trouble understanding our written words, but you may be a little shocked when you hear us speak! We pay very careful attention to our written French—terminology and sentence structure—but our spoken French is more... relaxed and has its own particular flavour! We guarantee you plenty of laughs trying to understand us, not to mention making yourselves understood (because you too have an accent that stands out in Québec!). To help prepare for your visit, we’ve put together a little lexicon.

While French is the primary language of instruction in our schools, English is also taught. Admittedly, not everyone has a flair for second languages, so you may chuckle over our accent when we speak to you in English. Unless, of course, you happen upon a Québecer whose mother tongue or language of use is English.… that is, until you hear them say things like “dépanneur” or “dep” when referring to a convenience store, or “close the light” for switch off the light, “chalet” for cottage, “terrasse” for patio, “cing-à-sept” (in French) for happy hour... Or they may claim to have been “in the moon” (spaced out) when they drove into an “ostrich nest” (massive pothole). As you can see, even Québec Anglos have a language all their own!

A blended language

From archaisms, neologisms, anglicisms, Québecisms, regionalisms and borrowings from other languages, you could say that Québec French has been woven together across time and cultures!

French is Québec’s official language, of use, signage, instruction and work (Bill 101, 1977). Neither a dialect nor a patois, it was brought by the first French colonists who arrived in New France between 1608 and 1760, mainly from Normandy, Brittany, the Paris region and Poitou.

Nearly five centuries later, our language has survived and evolved. Depending on people’s age and region, tonalities and pronunciations can vary, like in any other country. We use different expressions and our accent can come as quite a surprise to anyone unfamiliar with it, but this is less and less the case since Québec’s culture and talents now reach far beyond our borders. We even have a star—Céline Dion—who has toured the world in both French and English. Enjoy discovering a Québec that is rich in colourful expressions!

Indigenous languages

In Québec, nine of the ten Indigenous languages are commonly used to communicate. Sadly, Wendat is no longer spoken. These languages, full of imagery, have inspired the toponymy of more than 12,000 places in Québec. In fact, close to 10% of our official toponymy derives from Indigenous languages.

Examples: Québec (from kebec, an Algonquin term) means “where the river narrows”; Saguenay (Innu term) means “outflowing water” or “source of water”; Gaspé (derived from the Mi’kmaq word gespeg) means “land’s end”... You can meet First Nations Québecers and experience Indigenous traditions.

Where? There are 11 Indigenous communities spread across 55 localities. The Inuit, the masters of the North, are established in 14 communities along the shores of Nunavik.

Dur de comprenure?*

Québec lexicon

Here are some French terms and expressions we use in Québec. They include some ‘false friends’ (French words that don’t have the same meaning here) and anglicisms. Keep in mind that not everyone uses these words.

- Using the “tu” (instead of “vous”) form of address is common in shops and restaurants. And the word is often repeated twice in a question, e.g. “Tu viens-tu de la France?” (Are you from France?). The “vous” form is generally used for addressing people older than you, or people in positions of authority.

- When you say: “Merci!” (thank you) you’ll get a “bienvenue!” (you’re welcome) in return, or possibly an “avec plaisir” (with pleasure) or “de rien” (it’s nothing).

- “Valise de l’auto” (trunk of the car).

- “Barrer la porte” (lock the door), “revirer de bord” (turn around), “chauffer un char” (to drive a car).

- “Souliers” (shoes), “espadrilles” (running shoes), “tuque” (hat), “mitaines” (mittens), “foulard” (scarf), “combines” (long underwear), “gougounes” (flip flops).

- “Débarbouillette” (washcloth).

- “Facture” (restaurant bill; store sales receipt).

- “Magasiner” (shopping; shopping around for the best deal).

- “C’est tiguidou!” (It’s all good! Awesome!).

- “Chocolatine” (chocolate croissant; while the debate rages on in France over “chocolatine” vs. “pain au chocolat,” here in Québec “chocolatine” wins out).

You’ll see, we really have the gift of the gab! Now you’re all set to fall in love with Québec!

*Dur de comprenure = difficult to understand

Customs and traditions

The cliché of the typical Québecer is a clever mix of Latin “joie de vivre,” Anglo-Saxon pragmatism and Indigenous sensitivity to the changing seasons! This means we love to party (we’ve got festivals galore), we line up at bus stops in Montréal (but not in Québec City... too Latin!) and we talk non-stop about the current weather… as well as last year’s weather on the same date, and next winter’s weather too. It’s all related to our need to know how to dress!

We’ve got many other customs too, some of which are handy to know especially if you’re visiting for the first time:

Popular holidays

Québec’s statutory holidays and other popular celebrations throughout the year are: Christmas, New Year’s Eve, Easter, Saint-Jean-Baptiste day, July 1 (Canada Day, known for being moving day), Labour Day, Thanksgiving, Halloween (not a statutory holiday but celebrated nonetheless!).

Garage sales

Come spring, Québecers clean house, often in preparation for an upcoming move. They hold garage sales (or yard sales) to off-load all sorts of things, from clothing to household items. The garage itself isn’t for sale, but all the stuff stacked inside it and other unused items gathering dust in the house are! You’ll see long tables covered in all kinds of things… of no use to some people, but considered treasures and great finds by others!

Mealtime

Like our ancestors and Swiss and Belgian cousins, in Québec the French word for lunch is “dîner” and dinner is “souper.” Breakfast is called “déjeuner” (sometimes “petit” (small) déjeuner, but it’s rarely a small meal, and can be even heartier if it’s a brunch). Weekend brunches among family and friends—typically around 11 a.m. on a Sunday—can usually tide you over until dinnertime, at 6 or 7 p.m.

Restaurants

Good to know: many unlicensed restaurants (no liquor licence) advertise “Bring your own wine or beer.” So stop off at the Société des alcools du Québec (SAQ) to buy yourself a nice bottle. The restaurant will open it and serve it to you free of charge.

Upon arrival at the restaurant, you’ll notice two things: the server will bring you water and sometimes bread, and will ask you if you want separate bills. At the end of the meal, they’ll check again about the number of bills. Generally in Québec, people go Dutch. Men don’t systematically pay for their partners, which continues to cause a certain awkwardness, but we won’t get into that dynamic right now.

As for the bill, for more information on this topic, refer to the Taxes, service and tips section.

Units of measurement

Québecers seem to be of two minds, having recorded information from our two main forebears, the French and the English. While we officially switched to the metric system in 1970, we still flit back and forth between metric and British Imperial units. Here are some examples:

At the grocery store, all weights are metric but product labels indicate the conversion to pounds in small print. People never refer to 454 grams of butter, but rather to a pound of butter. When we talk about weight, we also talk in pounds, but younger people talk more in kilograms.

On the road, everything is metric. Distances are marked in kilometres and it’s clear for everyone. No one drives 100 miles/hour anymore. Thank goodness because 160 km/hour is considered speeding (the limit is 100 km/hour).

Metric is out the window when it comes to construction materials and everyday items like computer screens and sheets of paper, which are measured in inches. Much like people’s height: 5 feet 2 inches, six feet… instead of 1.57 m and 1.80 m.

The best example of binary thinking is the way we refer to temperature: our ovens are in Fahrenheit (350°F = 180°C), the water in swimming pools or other bodies of water is warm at 80°F (26.5°C), but we have no idea what 45°F or -38°F means because we use Celsius when we talk about the weather.

Québecers have virtually developed a form of “bilingualism” for units of measurement!

Québec names

Most French-sounding surnames stem back to the New France era (1608-1760). The colonists arrived mainly from Normandy, Brittany, the Paris region and Poitou. Surnames are often derived from nicknames reflecting the place of origin (Lafrance, Normand, Potvin – distortion of Poitevin), trades (Boucher, Boulanger, Cloutier) or a characteristic (Leblond, Belhumeur, Jolicœur, Legrand).

Québecers are fond of genealogy, as are many English Canadians and Americans who have French-Canadian ancestors. The archives have remained more or less intact since the beginning of colonization, supporting genealogical research and genealogical tourism, for example at the Maison de nos Aïeux on Île d'Orléans (Québec City area), the cradle of French America.

Surnames are now becoming more diversified thanks to immigration (newcomers account for 12.6% of the Québec population according to Immigration Québec). They often comprise both parents’ names, because since 1981, children can use either their father’s or their mother’s surname, or a combination of both. Also in 1981, Québec ruled that birth names are the only official surnames; as such, married women do not take their spouse’s name.